Stampfer, born in the highest hamlet on the old Tauern route between Matrei and the Tauernhaus, was the son of destitute parents who, as weavers, were forced to wander and only found shelter with relatives for the time of his birth. He attended school for the first time at the age of eleven, walked over the Felbertauern to Salzburg at the age of 17 and graduated from grammar school there with honours. In 1816, Stampfer was hired as an assistant teacher for elementary maths and physics at the Lyceum.

Stampfer is a teacher with heart and soul and is immensely popular with his students, which is an absolute speciality given the educational methods of the time. As he had to give his lectures in Latin, he published his own writings in German. His six-digit logarithm tables were soon familiar to every pupil in the monarchy and were used as learning aids well into the 20th century. In 1819, Stampfer was appointed full professor of pure elementary mathematics at the Lyceum.

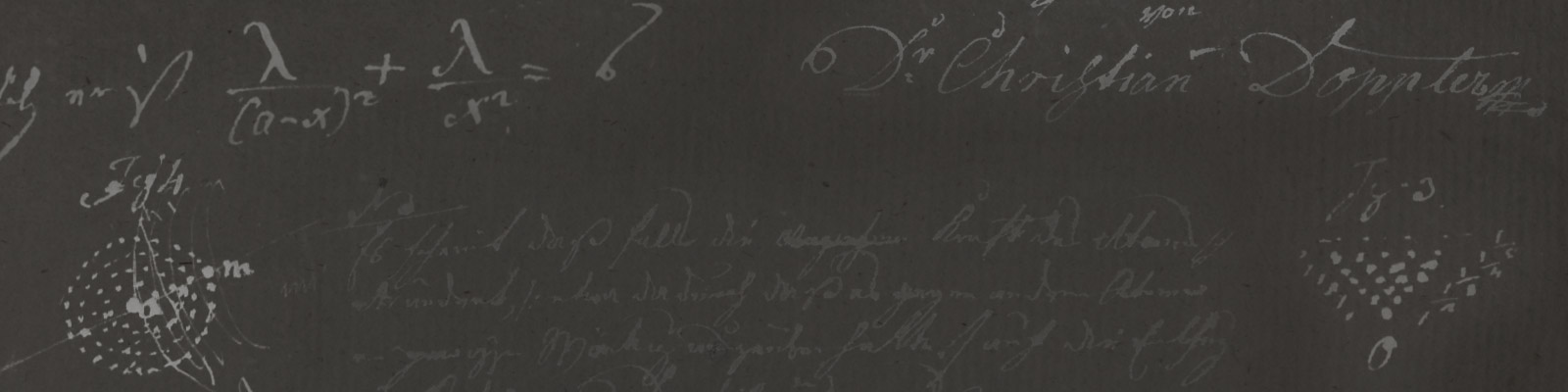

He set up an astronomical observatory in the tower of Mirabell Palace, “even though no one here in Salzburg has any concept or sense for it”, was able to put his knowledge of geodesy to the test when remeasuring the border between Salzburg, which had become part of Austria in 1815, and Bavaria and, when the chair of practical geometry at the Vienna Polytechnic Institute became vacant, he succeeded Franz Joseph Gerstner in 1825. Not only practical science was taught here, but also, as Doppler would later write, “scientific practice”. And that is why Director Prechtl had also brought Stampfer to the imperial city.

In the 23 years of his work, Stampfer would develop his scientific practice in the field of geodesy into a body of teaching that would remain authoritative far beyond Austria’s borders, even if it never bore his name. Stampfer would not discover a new physical principle like his student Christian Doppler, but he would make many improvements to measuring instruments. He was one of the first to recognise the need to give the optical industry a scientific basis. He became an advisor to Viennese opticians such as Plössl and Voigtländer, developed the dialytic telescope and even managed to ensure that Austria was no longer dependent on foreign countries for its glass supplies and that the first glassworks for optical glass was built in Vienna in 1844.

The coincidental coincidence of the beginning of Stamper’s work and the death of Joseph von Fraunhofer in 1826 became the outward sign of Fraunhofer’s successor; for what Fraunhofer had been for German optics, Simon Stamper now became for optics in Austria.

Stampfer’s personal fate was also similar to Fraunhofer’s. When Fraunhofer was fourteen years old, the building in which he worked collapsed and injured him under the rubble. Stampfer had also been hit on the head by a falling piece of wood as a child and suffered from it for the rest of his life, so that at the age of 58, when his right arm was completely paralysed, he still began to write with his left hand. The achievements of both scientists are verifiable, but their importance as technical and calculating opticians, from which the field of “precision mechanics and optics” still draws today, is difficult to prove due to the secrecy of the industry then as now. There is hardly an optical instrument that would have been created or improved without the help of both. They both had an influence on all developments in modern optics.

In the mechanical workshop of the Imperial and Royal Polytechnic Institute, he found a congenial partner, the mechanic Christoph Starke, with whom he developed an entire generation of new instruments for metrology and astronomy. His contribution is best illustrated by his correspondence with the director of the observatory at the Benedictine Abbey of Kremsmünster, Schwarzenbrunner, and Marian Koller, probably Stampfer’s best friend, who had worked in the Ministry of Culture and Education in Vienna from 1849 and with whom Stampfer had spent every Sunday lunchtime for 17 years. He improved the old devices, took care of the new orders and made inventions that significantly enriched astronomy. The workshop would not only produce prototypes, but also large series of instruments and thus gain a worldwide reputation.

In 1833, he invented stroboscopic discs and had them marketed in the same year under the name “magic discs”. This triggered such a huge stroboscopic frenzy that the edition was “sold out” within four weeks. But he wasn’t interested in business. For him, the stroboscope was a research task. He investigated its phenomena and thereby created the scientific basis for cinematography.

However, his levelling instrument, for which Stampfer received a patent in 1836, was of the greatest importance. During his lifetime, over 3,000 levelling instruments were produced and sold all over the world.

One of the highlights of his career was the founding of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in 1847, of which he was a member. Despite his retirement in 1848, he continued to lecture for two years and headed the institute until 1851, when his successor Christian Doppler was appointed to the first Chair of Physics at the University of Vienna.

After that, practically deaf and paralysed in his right arm, he rarely left his flat in Taubstummengasse. His son, Anton, died of pulmonary tuberculosis shortly after his appointment as Professor of Practical Geometry in 1850. Doppler’s teacher was not spared further heavy blows of fate. Three months later, his younger daughter, Barbara Maria, also died of pulmonary tuberculosis. Stamper’s wife was not to survive the death of their two children for long. She died in December 1856 and Simon Stamper’s eldest daughter Louise married Joseph Philipp Herr in 1853. Stampfer only kept in touch with these two spouses and a few friends, such as his former mechanics, father and son Starke, Father Marian Koller and Professor Kreil. But what an illustrious circle that was! When Stampfer died in 1866, the industrial age at the Polytechnic Institute and the “brief heyday of optics” in Vienna had come to an end. In 1894, “Stampfergasse” in Vienna-Hietzing was named after him.

Simon Stampfer and Christian Doppler

Simon Stampfer, who, in addition to his employment as a tutor at the Lyceum, was given a second job of the same kind at the grammar school in 1816, teaching maths, natural history, physics and Latin and Greek, advised Johann Doppler to give his son Christian a higher education. Christian is taught these subjects by Stampfer at the grammar school.

Stampfer provides suggestions and ideas that go beyond the subject matter, endeavouring to convey his knowledge in an understandable way and make the lessons entertaining. He knows how to inspire his pupils with practical demonstrations of the technical apparatus from the “physics cabinet”. Even during the holidays, he took his students on excursions to the surroundings of Salzburg, in particular to the Untersberg, Gaisberg and Watzmann mountains – “These were festivals for the students, in which it was considered an honour and a distinction to be allowed to participate; there was never a lack of material to teach them about barometric and other measurements,” wrote his later son-in-law Professor Josef Herr.

In the same year that Christian entered the grammar school, Stampfer must also have received permission to set up an observatory in the tower of Mirabell Palace. The tower had already gained importance in 1806 as a fixed point for surveying. Now it served Stampfer as an astronomical laboratory. We can assume that Christian used it to peer at the night sky through a flap in the dome. Stampfer regularly used the telescope to make astronomical observations and calculate comet orbits.

With great manual dexterity, he made barometers, thermometers and distance meters himself and allowed his pupil to watch. This room served as Stampfer’s laboratory until 30 April 1818, when the town fire gutted most of the old town on the right bank, and with it the tower. Fortunately, Stampfer was able to save all the instruments and records of the surveying work he had carried out when surveying the border between Salzburg and Bavaria.

When Stampfer became professor of elementary mathematics at the Lyceum in 1819, he requested to be relieved of his teaching duties at the grammar school from 1820/21. It is more than a coincidence that Doppler also attended the 4th grade of the German Normal School in Linz in 1820/21, the district capital at the time, which may have been roughly equivalent to the lower 4th grade of a modern-day secondary school. The school was located at Hofgasse 23, where Anton Bruckner and Rainer Maria Rilke also went. A memorial plaque was erected in 2003.

After graduating, Doppler moved to Vienna in 1821 on the recommendation of Stamper, where he took up studies in mathematics, physics and geometry at the Polytechnic Institute, now the Technical University. Josef Hantschl (1769 – 2 June 1826), professor of pure and higher mathematics, knew how to make the results of mathematics useful for life. His academic success was consistently good. His exemplary behaviour, diligence and progress in his studies were particularly praised. Doppler is said to have received a medal with the inscription ‘WERDE NÜTZLICH’ from Stampfer as a reward for good academic performance while he was still at school in Salzburg.

After his exams, Doppler applied for an assistant position with Hantschl, but Hantschl felt that Doppler was not yet fully trained in maths, despite his excellent grades. Doppler therefore decided to return to Salzburg to catch up on his A-levels at the Lyceum.

In the meantime, Stampfer, who had been forced to realise that he could not progress academically in Salzburg – the Lyceum had been downgraded to a “second degree” Lyceum – was able to win the bankruptcy against numerous competitors in Vienna and become a professor at one of the most outstanding universities in Europe in 1815.

In 1832, the Society of German Physicians and Natural Scientists met in Vienna for the first time. Doppler attended the meeting as a guest, at which Stampfer presented a new instrument, the optometer. It is still used almost unchanged today to measure the refractive power and accommodation width of the eye, i.e. to determine the spectacles required for the eye.

On 24 February 1849, Doppler came to Vienna as the successor to his teacher Stampfer. Stampfer’s highly talented son, Anton (1825-1850), became his assistant – the pride and joy of his father and chosen by Doppler to continue as his successor when he became the first director of the university’s newly established Institute of Physics. However, Anton died in 1850 and Stampfer, Doppler’s first teacher, continued to teach his pupil Doppler for another two years, supported by his assistant Joseph Philipp Herr (1819-1884), his later son-in-law, who was elected the first rector of the Polytechnic Institute in 1866.

Dr. Peter Maria Schuster, 2017