Franz Serafin Exner studied philosophy from 1818 to 1821 and law in Vienna and Padua from 1822. After gaining his doctorate in Vienna in 1827, he was a teaching assistant for education and philosophy until 1831. Leopold Rembold (1785-1844) had awakened his interest in philosophy, and his influence became decisive for Exner’s direction in life. It was painful for Exner to become the deputy of his teacher in 1830-1831, who had been suspended in 1824 for “erroneous principles, obscurity and inappropriateness of his lectures”. Professor of philosophy in Prague from 1832, Exner became the most popular of all professors there after barely eight years. According to his grandson, the Nobel Prize winner Karl von Frisch, who collected several statements such as: “The better ones among us left the hall in a state of emotion and excitement that resonated in their minds for a long time and had a lasting influence on their character and intellectual development”.

Franz Serafin Exner studied philosophy from 1818 to 1821 and law in Vienna and Padua from 1822. After gaining his doctorate in Vienna in 1827, he was a teaching assistant for education and philosophy until 1831. Leopold Rembold (1785-1844) had awakened his interest in philosophy, and his influence became decisive for Exner’s direction in life. It was painful for Exner to become the deputy of his teacher in 1830-1831, who had been suspended in 1824 for “erroneous principles, obscurity and inappropriateness of his lectures”. Professor of philosophy in Prague from 1832, Exner became the most popular of all professors there after barely eight years. According to his grandson, the Nobel Prize winner Karl von Frisch, who collected several statements such as: “The better ones among us left the hall in a state of emotion and excitement that resonated in our minds for a long time and had a lasting influence on our character and intellectual development”. Exner taught in Prague for 17 years – until his appointment as a ministerial councillor in the Ministry of Education in Vienna in 1848. In 1840, Exner married Charlotte Dusensy (1816-1859), who, as the daughter of a wealthy Prague merchant, was able to run a convivial house. Exner’s salon brought together “like an academy the most learned and sharpest minds in Prague”. They read poetry and philosophy, especially the works of the philosopher, pedagogue and psychologist Herbart (1776-1884). Exner became widely known academically above all for his criticism of Hegel.

In 1848, he returned to Vienna as a ministerial councillor in the Ministry of Education (Department for Teaching Reform), where he played a key role in the reorganization of the university system from 1849 to 1851 under Minister Leo-Graf von Thun-Hohenstein, who had been his student in Prague, dealing with the freedom of teaching and learning and the combination of research and teaching. He turned down the offer of a ministerial post several times. Already seriously ill, he went to Upper Italy in 1852 as ministerial commissioner for the Lombard-Venetian school system in order to pursue academic reform in those provinces, which at that time still formed part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. As a result of a rapidly progressing lung disease, he died prematurely in Padua in 1853.

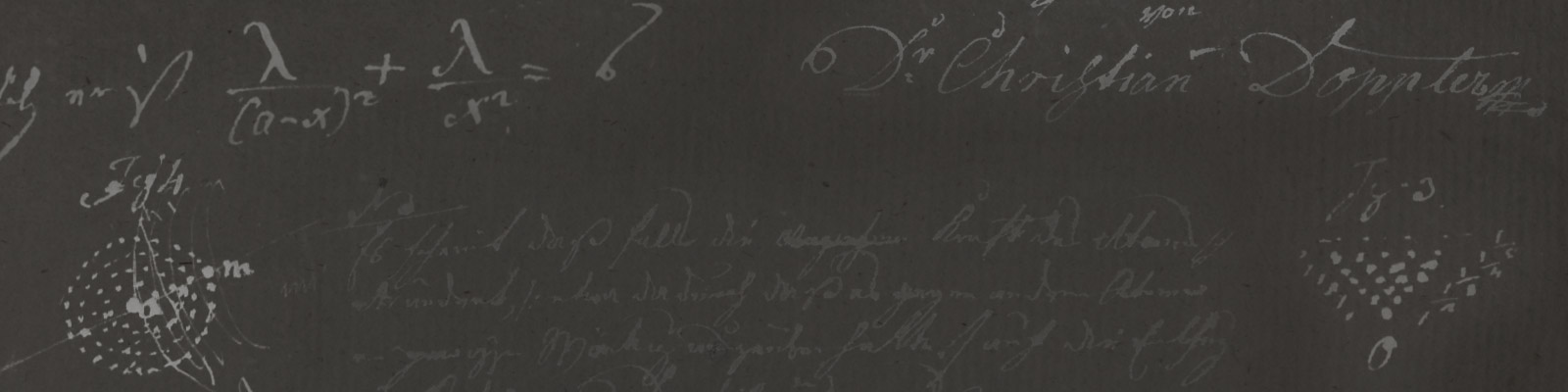

Franz Exner and Christian Doppler

Doppler’s close friendship with Franz Exner, in whose hospitable house at Roßmarkt 1282 he immediately felt at home and made important acquaintances (Father Schneider, Franz Palacky and Leo Graf Thun-Hohenstein), was of great importance for his life and work. There is evidence of his contact with Exner as early as the winter of 1836. On February 6, 1837, he wrote to Bolzano: “I have finally decided to take up higher mathematics, and our brave Doppler is helping me. I have also begun to study anatomy and physiology with him, from books in front of me.” Exner will be present at many of Doppler’s lectures in Prague.

When Doppler returned to Vienna in 1849, where he had begun his career as an assistant, fundamental reforms in the field of education began under the new Minister for Cultus and Education, Count Leo Thun-Hohenstein – the draft for which came from Exner and the Berlin philologist Hermann Bonitz. This reform finally brought Doppler what his friends had hoped for. On January 17, 1850, the nineteen-year-old Emperor Franz Josef I – Count Thun’s paper had presumably been drafted by Exner – approved the establishment of the Institute of Physics at the University of Vienna and appointed Christian Doppler as its first director.

In October 1851, when Doppler moved into the new institute, Exner was forced to take a vacation. Count Thun had written to him several times urging him to take it easy. Exner chose Venice as he hoped to recover there and used his stay to write a report on the state of the Lombardy-Venetian grammar schools. This formed the basis for the reorganization of the Italian academic system, which the Emperor sanctioned in October 1852. Exner hurried to Vienna in the same month and tried to influence the mood in the Academy in favor of Doppler. However, after falling ill, he had to ask for a new six-month leave of absence. He traveled to Venice together with Doppler, but did not stay long, instead continuing on to Pavia because, like Doppler, he felt that he did not have much time left and that he would therefore have to work all the more intensively. He died on June 21, 1853, four months after his closest friend Doppler.

Dr. Peter Maria Schuster