Petzval’s father was an original, not only as a teacher and composer – masses composed by him are still performed today – but also as a skilled mechanic, which earned him the nickname of a magician. As chance would have it, one of his two other sons was also born on January 6th, just like his son Josef – his third son was born on January 7th. This fact earned them the joking name: the Three Kings.

Josef Petzval received his engineering diploma from Pest University in 1828, of which he was particularly proud. In 1830, his dam calculations saved Pest from being flooded by the Danube. While still a professor, he preferred the title “Graduate Engineer” to all other titles, even his doctorate, which he obtained in 1832. From 1835 professor of higher mathematics at Pest University, from 1837 to 1877 professor of mathematics and mechanics in Vienna.

Josef Petzval made great contributions to the further development of photographic optics. In 1839-57, he designed two types of lens for portrait photography, which exceeded the light intensity of the lens used by Daguerre by a factor of 16, and for landscape photography, which also represented a decisive advance in terms of resolution and achieved worldwide fame. For the practical implementation, he initially worked together with F. v. Voigtländer, with whom there were soon differences and a final break in 1845, which was followed by legal disputes in 1857/58. This was decisive for Voigtländer moving his production to Germany in 1868, when he had already delivered over 100 workers and the 20,000th portrait lens.

As a mathematician, Petzval gave unusual lectures, for example on the theory of tone systems, developed a 31-step tone system for which he constructed a piano to prove the correctness of this system, as well as a stringed instrument which he called a guitharve. He used to introduce his acoustic lectures with the saying: Mathematics is the music of the mind, music the mathematics of feeling. He read about the theory of swordplay – he claimed that the Austrian cavalry sabre was not properly constructed – and about the theory of horse gait. In summer, he used to ride to his lectures in the city from his home on the Kahlenberg, a Camaldolese monastery abolished by Joseph II, on a genuine Arabian black horse, split a certain amount of wood next to the house every day, performed physical exercises which the Viennese were completely uncomprehending of, and was considered the best and most feared sabre and rapier fencer in Vienna.

The most important of his manuscripts, which concerned dioptric objects, were lost in a burglary at his home. The loss hit Petzval so hard that he withdrew from all society afterwards. He was unable to decide to replace the papers. At the age of 62, Petzval married, but his wife died just four years later. The Academy, of which he was a full member from 1849, remained the only place where he could still be seen in his old age. He remained loyal to it, just as it had remained loyal to him in all the many controversies he had to fight out – not least because of his critical, argumentative and sarcastic nature. Retired in 1877 with the title of Court Councillor, he hardly ever left his apartment, did not want friends to visit him and became a recluse in the middle of Vienna.

Josef Petzval and Christian Doppler

Until Doppler’s appointment as Director of the University’s Institute of Physics in 1850, no criticism of his theory had been voiced from Vienna – the main work had not even been acknowledged.

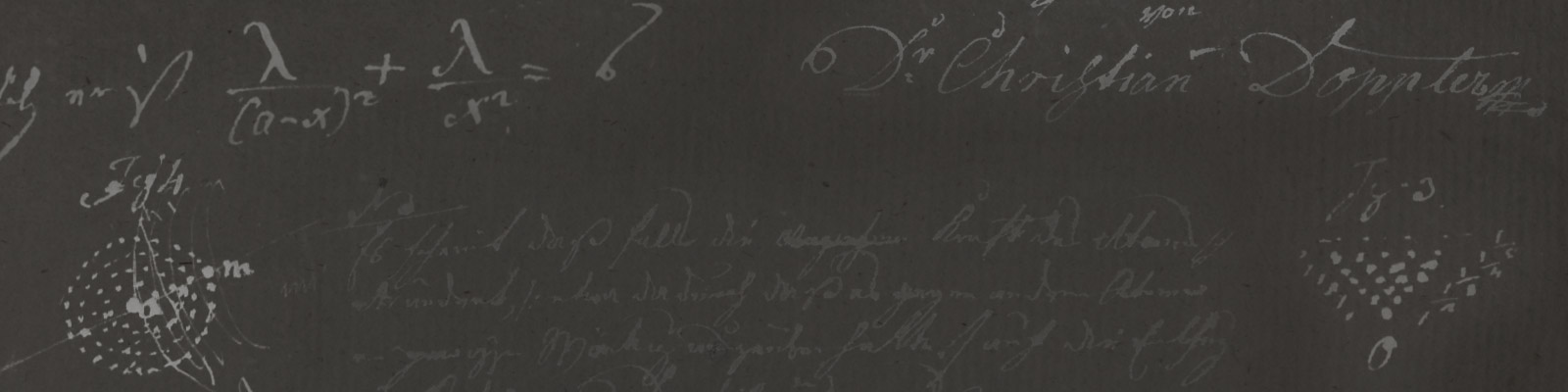

Ten years after his discovery in 1842, a fierce polemic about the validity of the principle began in Vienna. The dispute was started by Josef Petzval, who, however, as he himself admitted at the meeting on October 21, 1852, was only the chosen exponent of a large number of scientists. Petzval’s first attack on January 22, 1852 begins with the words: “One can say that there is a great and a small science, just as there is a great and a small war.“

Petzval mockingly classifies Doppler’s principle in the second category, small physics, to which Doppler replies in the meeting on May 21:

Newton. Leibniz, Euler, Laplace, Poisson, and all the men of immortal name whom we are accustomed to regard as our masters and teachers, never made such a distinction! – Rather, untouched by scientific arrogance, they regarded every new truth as equally worthy of attention and recognition.

In this first lecture, Petzval warns that it is impossible to enter the great science without an understanding of differential equations:

The remaining part of the human race, however, must again be fobbed off with analogies taken from ordinary life and found by the little science; inventive partisans then again do not fail to extend this analogy beyond the limits of its validity: thus the old reign of error threatens to break in anew in an altered form, unless the spirits of differential equations take care of us and free us from it.

Doppler replies in his lecture: “Does Mr. Opponent mean that a natural phenomenon which cannot prove the justification for its existence from these equations must be regarded as non-existent for science?“

Doppler defended himself properly and correctly in this dispute and, as others have already noted, his statements can be seen as a model of scientific controversy. The actual scandal occurred in the second dispute, in the meeting on May 21, 1852, at which not only the President of the Academy, “His Excellency” Ritter von Baumgartner, was present, but also 33 guests in addition to 24 actual and four corresponding members, a total of 62 listeners. It was an unusual measure to set up such a high-ranking special commission to assess the case. In a kind of showcase procedure, the two authors each gave a presentation. At the beginning, Petzval tried to justify his approach from January:

Do not think, therefore, that I could decide to attack a number of more or less useful views of popular science merely in order to raise the value of my own analysis; I have another, much more important reason: for I am imbued with the conviction that one can hardly do anything more meritorious than to reject within due limits the excessive endeavor to popularize that is attached to popular science, because the history of science has taught that it is by no means conducive to the progress of the same, but rather, directly as well as indirectly, brings harm.

Petzval then sums up his objections in an anti-Doppler formula: If the sounding body vibrates the tone A when at rest, it will not only continue to sound A when set in motion, but it will also emit the same tone A and no other to the surrounding medium.

The decision in the Vienna oratorical duel was made in the third round on October 21, 1852, not by force of superior arguments, but by force majeure: Doppler’s illness. Petzval was not distinguished enough to continue to ridicule the principle in his third speech – one week before the seriously ill Doppler left for the south, which was seen as a defeat by the public:

One cannot say of Doppler’s theory that it has no value precisely because it gives a decidedly incorrect account of the process of a phenomenon; it must rather be asserted that its value is a negative one, because it has misled so many followers of science into error by an apparent simplicity and clarity which, however, is nothing more than superficiality and lack of depth.

As already mentioned, Petzval considered Doppler’s theory to be abthane, demonstrably erroneous. And although the principle had been experimentally confirmed several times by this time, the majority of the academy agreed with Petzval’s damning verdict. Only Ernst Mach was able to resolve the controversy in a plausible way in papers published in 1860 and 1861:

The principle of the conservation of the period of oscillation (Petzval) states that in a permanent flow in a medium, if oscillations are excited anywhere, the period of oscillation is the same, i.e. constant throughout, at any location that is invariant with time. – Doppler’s theorem teaches the dependence of the period of oscillation on the relative speed of the wave source and the observer. Both theorems therefore refer to different cases……The application of Petzval’s principle to Doppler’s case is based on a misunderstanding. In his mathematical deduction, Petzval thinks he can replace the relative movement of the wave source and the observer with a flow of the medium, but this is inadmissible.

In popular terms, the relationship between Petzval’s and Doppler’s laws could be illustrated as follows. If Prof. Petzval were serenaded for the invention of his Principle, for example, it would sound up to his windows in the same key, just as harmoniously and melodically as on the most beautiful May morning, even in less pleasant weather. According to Doppler, on the other hand, a chorus in E major could be heard in F major as it descends from the heights.

Despite this clarification by Mach, which refuted Petzval’s objections, and several experimental confirmations, the principle continued to be contested for another 20 years.

It is a strange coincidence that on November 6, 1901, the Petzval celebration took place at the University of Vienna, where, at the same time as his monument, that of Christian Doppler, whom he had fought so fiercely against during his lifetime, was unveiled in the arcaded courtyard of the university, with a ceremonial speech for Petzval and for Doppler.

Dr. Peter Maria Schuster, 2017