Kreil attended the Stiftsgymnasium in Kremsmünster from 1810-19, where he assisted P. B. Schwarzenbrunner with astronomical and meteorological observations at the observatory there. 1819-27 he studied at the University of Vienna, first law for 2 years, then mathematics, physics and astronomy. 1827 assistant to Littrow at the Vienna Observatory, 1831 employed at the Brera Observatory in Milan, where he began geomagnetic measurements in 1836. 1838 assistant, 1845 director at the observatory in Prague. He endeavored to restore the observatory, which had fallen into disrepair, with instruments that he bought from his own savings. Although he was only able to set up his observatory in an ordinary room, after just a year and a half it took first place after the one in Göttingen. His observations earned him the highest recognition from Gauss, Humboldt, Sir J. Herschel and others. He deserves credit for having carried out the first magnetic surveys not only in Austria, but also in the Balkans, Turkey and the Adriatic region. He provided the material on the basis of which a theory of geomagnetism could be developed. In Prague, he developed a plan for a meteorological observation network and, as he lacked staff, for the construction of recording devices for air pressure, temperature, wind, humidity and precipitation.

From 1847 member of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna. In 1851 he became the first director of the newly founded Central Institute for Meteorology and Geomagnetism in Vienna. He was also appointed professor of physics at the university at the same time. He was also obliged to “give lectures on the results of his research at the University of Vienna, insofar as his initial obligations as director of the meteorological institute allowed him to do so”. This marked the beginning of a new era. Kreil became the founder of the great tradition of Austrian meteorology and geomagnetism.

Karl Kreil and Christian Doppler

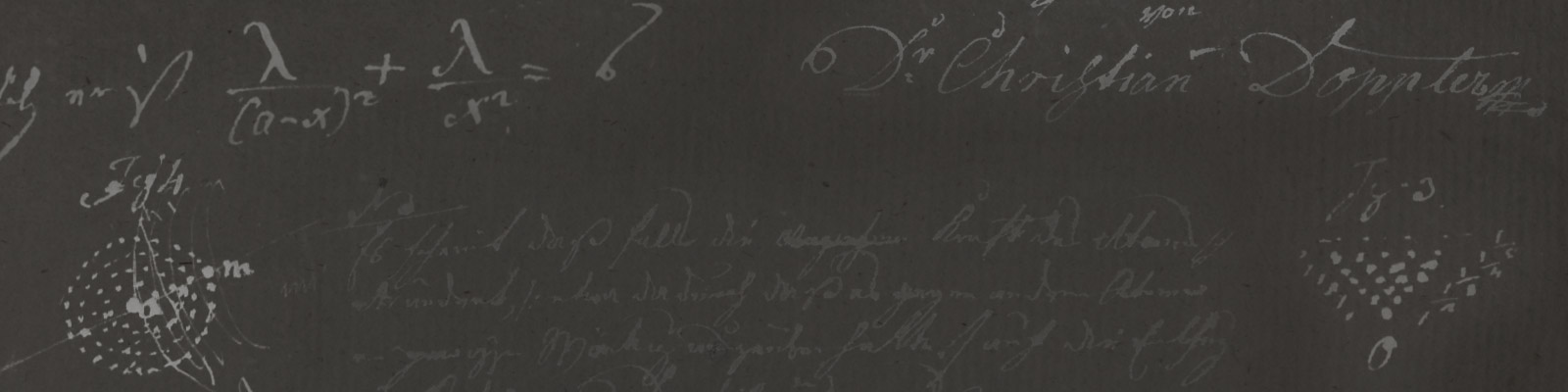

Kreil was present at the meeting of the mathematical section on Nov. 5, 1840, which Doppler attended for the first time, as well as at the second meeting on Dec. 3, 1840, at which Doppler made critical remarks about Kulik’s essay. Kreil attended all of Doppler’s other lectures, with the exception of the lecture at which Doppler presented his principle, which was later named after him. Nevertheless, like Bolzano, he uncompromisingly supported this principle and in the “Astronomisch-meteorologisches Jahrbuch für Prag, Dritter Jahrgang 1844. Prag 1843” in an essay: “Dopplers Erklärung des farbigen Lichtes der Doppelsterne und einiger anderer Gestirne” (Doppler’s explanation of the colored light of double stars and some other celestial bodies) he endeavored to provide acoustic evidence. He uses the railroad to introduce large terrestrial velocities and thus theoretically anticipates the experiments of the Dutch physicist Buys-Ballot from 1845.

In 1845, Kreil wrote an unusually laudatory tribute to Doppler in the journal “Österreichische Blätter für Literatur und Kunst” entitled: “Christian Doppler’s scientific achievements”. Unusual because the journal had never before or since published a portrait of a scientist during his lifetime. It states that “Doppler’s work is unmistakable, and each of it has its own peculiar value, as it draws attention to some truth that has escaped previous research and derives the most useful applications from it through the most astute, often quite surprising conclusions”.

Kreil was also present when, on May 20, 1846, Doppler presented a paper at the meeting of the “Section for Natural Sciences and Applied Mathematics”, probably in a first version, which his grandson, Adolf Doppler, will find in his estate. The minutes state: “In a free lecture, Mr. Doppler spoke about the possibility of experimentally determining the absolute states as well as the absolute number of individual molecules constituting a solid body”.

Kreil married Mathilde von Pflügl, the sister of Hermann von Pflügl, in 1851. The latter had married Mathilde Doppler, the eldest daughter of Christian Doppler in his second marriage. Kreil had thus become the brother-in-law of Doppler’s daughter. After Doppler’s death in 1853, Kreil was co-guardian of Doppler’s children, providing educational and perhaps occasionally also material support.

We also have Kreil to thank for the important obituary of Doppler in the “Zeitschrift der Gymnasien”. It reads: “The famous British astronomer Herschel sent Christian Doppler the rare and precious work containing his astronomical observations at the observatory on the Cap as a token of his appreciation for his ingenious discovery”. It is the only information we have received about this remarkable international recognition. The book by Sir John Frederick William Herschel is entitled “Results of Astronomical Observations Made at the Cape of Good Hope” and was published in London in 1847. It cites the discovery of a series of double stars.

Dr. Peter Maria Schuster, 2017